The reflection of the modernist movement, which emerged in the late 19th century, in architecture presents itself as calm and minimalist products in terms of both form and color. This approach, which was adopted by the modernist movement and its pioneers, focusing on the primary function of the structure, has been combined by modernists with other concerns and needs related to beauty. It can be said that this simple, calm, and serene creation approach in modern buildings is particularly perceived as ‘beautiful’ by the 21st-century individual. To better understand this conclusion, we can point to the fast-paced, scheduled, and repetitive lifestyle of people in this century as an example.

It is possible for a person who wakes up at a certain time, works within specific hours, eats at designated times, and has to be quick in order to make time for both themselves and their social life—living dynamically—to feel discomfort when faced with a building whose entrance is hidden, with narrow, long, dense windows, and a facade that constantly tries to communicate something rapidly, as if in a hurry. The design of such a structure might unconsciously or consciously reflect their own way of life. On the other hand, the same individual might feel more at ease in a building where the entrance is centered, surrounded by glass, with square or rectangular windows, and a facade that remains silent and calm, as if it does not want to make noise, offering a quieter and more peaceful atmosphere.

- “To find something beautiful means to see our thoughts about what a good life should be like materialize on an object.”

(Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness)

A building that appears beautiful and gives a certain feeling may not be considered beautiful if it fails to perform its function properly. For example, if a house built in a modern style does not provide thermal or acoustic comfort in its living spaces, if its roof is not suitable for the climate of the region, and it causes problems for the user, we cannot say that the house is beautiful. A chair with simple lines, in shades of gray, and which impresses viewers, would not be considered beautiful if it does not serve its function of seating or causes issues for the user. Despite the feelings it evokes through its appearance, we cannot say this chair is beautiful. This implies that not every modern product is necessarily beautiful.

On the other hand, trying to understand modernism and the products that emerged under its influence solely through the lens of people with a particular lifestyle, living in a specific time period, would also be incorrect. Modernism, like all other art movements, is a universal concept. The world is home to different cultures, beliefs, languages, and values. Therefore, like other concepts in architecture, we cannot say that the understanding of beauty has a definitive answer.

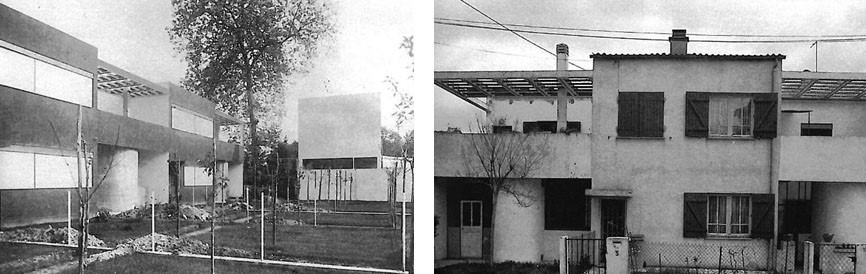

- In 1923, a French industrialist named Henry Frugés asked architect Le Corbusier to design housing for the workers and their families at his factory. The housing units, built next to his factories in Lége and Pessac near Bordeaux, are monuments of Modernism, with their boxy appearances, long rectangular windows, flat roofs, and walls.

…

However, the sense of beauty of those who would live in these houses is quite different from his.

…

The people who would move into these houses must wear the same blue overalls every day, work in huge hangars, and fill boxes made of pine wood with candies. Many of them have left their homes in nearby villages to work at Mr. Frugés’ factory, and so they long for their homes, villages, and fields. Once their shifts are over, the last thing they wish for is for the place they return to, which they call home, to remind them again of the industrial world.

(Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness)

The architects, painters, and other artists who supported the ornate and detailed approach of the Gothic style as beautiful and right clearly had a different understanding of ‘beauty.’ For them, beauty was found in soaring towers reaching toward the sky, numerous colorful windows, and intricate decorations.

- According to Keene, the Japanese sense of beauty was distinctly different from that of the West. In Japanese aesthetics, there was a preference for irregularity over symmetry, impermanence over eternity, and simplicity over ostentation. ‘What causes this is neither climate nor genetics,’ Keene added. It is the actions of Japanese writers, painters, and theorists that have shaped the Japanese perception of beauty.

(Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness)

- Architecture is a very distinct art. This is because nations have such diverse religions and traditions that what is suitable and normal for one country may not be so for another.”

(Tomaso Temenza)

The evolution of the perception of beauty must also take into account the individual’s own transformation. Just as the insights we gain from reading a book vary depending on our age, and just as a song evokes different emotions depending on our mood, time, or place, whether a building or a work of art is beautiful to us can also change over time with our experiences and personal growth.

The house we were born and raised in may not seem beautiful to us while we live there with our family. However, after moving away and returning years later, we no longer see just the building itself—we see the memories we lived within it. The door we slammed in frustration, the windows that carried our laughter into the street, the walls around which we ran and played—suddenly, they all appear different to us. This can make that house ‘beautiful’ in our eyes. The house itself has not changed; its doors, windows, and even its façade remain the same. What has changed is our perspective and the emotions it now evokes in us.

- In 1965, I was in Berlin, and I remember visiting Otto Frei. The port city of Bremen had been artificially constructed, with some openings or windows made translucent, using sandblasted glass. Otto Frei said that by doing so, he had removed all the houses with roofs from view—because he could no longer bear to see the traces of the past.”

— Philippe Sollers

A building constructed with a modernist approach may seem meaningless, unattractive, or even ugly to us at one point in time. However, as the years pass and memories accumulate, that same building may come to represent our meetings with friends, and we may begin to find it beautiful. Similarly, we may once admire a Gothic-style structure, yet if we experience the worst moments of our lives within its walls, we might later perceive it as anything but beautiful.

Ultimately, architecture, by its very nature, is a discipline that places humans at its core, drawing from their emotions and thoughts. As a result, architecture, always intertwined with art, compels the architect to consider not only the functional needs of the time but also the psychological and emotional impact of a structure on its users. The modern is born with the intention of being beautiful within its era—through its form, texture, color, and composition. Yet, in time, what is considered ‘modern’ will inevitably belong to the past, losing its modernity for future generations. However, for those who share a common perspective through a universal lens, the modern will always remain beautiful.